Detention of ex-Everton Star Li Tie Sparks Biggest Government Crackdown in a Decade

by a SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT

China Sports Insider is delighted to publish the following contribution from a special correspondent, who wishes to remain anonymous. All details contained in this article have been translated from Chinese-language reports published on well-known Chinese websites, including official announcements on people detained for investigation etc.

PART 1 – The Online Sacrifice of a Greedy Icon

Like all good football corruption enquiries, the shocking criminal investigations playing out this winter in China started with complete silence. Early last November, one of the biggest stars in Chinese football disappeared. From a training session. According to reports, he told the other participants that he was going to “take some pictures”. He probably added, “I may be some time”.

Li Tie, the former national team player and manager then stopped posting to Chinese social media platform Weibo. He has not replied to his WeChat messages and his phone has been switched off ever since. If that happened to Cristiano Ronaldo for even an hour his followers would be rightly worried for him.

But the Chinese public has been raised on football scandals, so there was no concern at all for one of the game’s most famous characters. The immediate assumption for his sudden absence was universally shared. “Corrupt, 100%,” texted one million fans, Liverpool supporters adding sarcastically, “That’s what they teach you at Everton”. The Merseyside club was home to Li Tie (or ‘Lie Tie’ as he became known locally) for the two seasons he played in the Premier League from 2002 to 2004.

Li’s detention was big news in China and reporters immediately made good use of usually heavily-censored “self-media” channels – their own blogs and platforms – to trash him with speculative wrongdoings. It would be remarkable if one man could actually cram such voracious pillage into one career.

But this is Chinese football and few of the outrageous claims can be discounted completely.

Li’s remarkable downfall was set in motion while he was national team coach from 2020-2021. During his time in the hot seat, he famously led Team China on the road to failure in the 2022 World Cup qualifying campaign. He was sacked, but it all ended with a dismal 3-1 loss to Vietnam anyway.

On his initial appointment, the Chinese Football Association (CFA) revealed his annual salary was RMB 8 million ($1.18 million). It was widely considered too high for a local coach with no international management experience.

Fortunately for Li, he was still managing at Chinese Super League (CSL) club Wuhan Zall in Hubei province. He had done well to take it up into the top flight on a salary of RMB 12 million ($1.77 million) and was by then receiving a much more lucrative RMB 30 million ($4.42 million) from the club. Li decided that he deserved both salaries. After all, it would be he who led China gloriously to the World Cup Finals for the first time in two decades. For a while, Wuhan owner Yan Zhi played along, figuring he was contributing to China’s wider interests and those of the country’s football-loving President Xi Jinping.

Lockdown Crisis

Like all other clubs, Wuhan Zall was struggling for cash during COVID lockdowns. Boss Yan asked Li to take a pay cut. After all, it was a remote, part-time role. But rather than accept this reality, Li is reported to have called in CFA President Chen Xuyuan to arbitrate in his salary negotiations. Chen was appointed to make a success of pre-pandemic reforms that everyone could see had been failing due to wild spending.

Then, with Wuhan boss Yan resisting payment of Li’s salary, and businesses and livelihoods crumbling all around, the CFA docked the club nine points – twice. What had it done wrong? Non-payment of wages! The result for the club was relegation and then liquidation. Some fans are calling it murder. And it really pissed off Yan.

In fact, the owner was so incensed that he boldly collected all the evidence he had against Li and delivered it in person to the authorities in Hubei. Although this meant Yan himself was detained for investigation, he seemed prepared to pay the price to bring Li down.

The Net Bulges

Li Tie’s official arrest by the fearsome Central Commission for Discipline Inspection on November 26 was an exciting diversion for millions of pissed off fans now watching happy maskless fans at the World Cup on TV. The realization that the rest of the world was not in lockdown anymore was a rude awakening and national broadcaster CCTV even tried, until it was rumbled, to edit out the crowd scenes.

Meanwhile, reporters started to work sources who knew about Li’s recent and distant past. The first question: who else is involved? Sure enough, stories of acquaintances whisked away by shadowy figures or invited for ‘a cup of tea’ – a euphemism for a summons from the authorities – broke across the Chinese internet. Over 20 people connected with Li did not come back home for their dinner. Months later, tea is still being poured for some of them. Somewhere.

The detained include Hu Guangyu, deputy director at the Political & Legal Department of the General Administration of Sport, China’s sports ministry. Oh dear. Also linked to Li Tie and unavailable for comment are former internationals Zhang Lu and Xin Feng, as well as coach Zheng Bin, all members of his inner circle. Former Wuhan FA official Fu Xiang is another who can no longer check the fixed football scores on his mobile. Yet others are linked with now relegated Guangzhou FC (formerly Guangzhou Evergrande), where Li served as assistant coach under Italy’s World Cup-winning manager Marcello Lippi.

Each of these announcements has prompted online dissection of old matches between the protagonists. How many of these games were fixed? In the general confusion over the sudden and chaotic ending of COVID restrictions, Li’s agent is reported to have quietly slipped away to Japan.

One of the key match-fixing allegations leveled by reporter Ran Xiongfei is the 2019 CSL match between Wuhan Zall FC and Shenzhen Kaisa FC, under Italian legend Roberto Donadoni.

Seen at the time as a classic, Wuhan took a 4-1 lead, only for Shenzhen to score three second-half goals in a four-minute burst. The game ended in a magical 4-4 draw. If this was the result of match-fixing, one still has to admire the players who scored some of the wonderful goals.

A strong reason for suspecting the final result is that the point enabled Shenzhen to finish second from bottom. Due to the widely predicted collapse of Tianjin Tianhai FC, Shenzhen thus retained its place in the CSL. Now, with six club officials among those detained, it seems Shenzhen could be the latest of over 30 professional clubs disbanded since the current CFA administration came into office.

Another of Li’s activities coming under scrutiny is his Shenyang Football No.8 Park. The land was originally allocated for a public facility to benefit local people. Via higher level relationships, Li and his partners are accused of having it accredited as a national training base. This status was then used to take control of the land.

The stories of Li’s greed now circulating without retort do not stop there. It is suggested he is hiding between RMB 100-300 million ($15-45 million) in a Shenyang bank account and has undeclared property assets in the UK and the US. As with all these claims, Li is not around to defend himself.

Jealousy & Greed

Other Chinese reporters have revealed that Li charged players RMB 3 million ($440,000) for selection to his national squad in an illegal pay-to-play scheme. But it is not the very idea that even Jude Bellingham needs to palm a brown paper bag – or red envelope, as would be the case in China – to Gareth Southgate to get a game for England that is surprising in China. It’s the rate of inflation. Before the Great Football Crackdown of 2010-2012, the rate card for selection to China’s national squad was revealed by Titan Sports to be just RMB 200,000 ($30,000).

Of most concern to football purists, some commentators submit that Li was jealous of the naturalized players controversially brought in to help strengthen Team China. He did indeed substitute them at strange times during the World Cup Qualifiers, typically when players like Ai Kesen (Elkesen), A Lan (Alan Carvalho) and Aloiso (Luo Guofu) seemed to be the most likely to reverse China’s fortunes.

If it is ever proven that his ego prevented Li from playing his best team in its most crucial matches since his own generation had reached the World Cup finals, it would be seen by the Chinese people as treasonous.

Li is also accused of running no less than nine football-related enterprises, some using youth training projects to launder money and evade tax. One of them was his own player agency. In one case, he is suspected to have approved a big pay rise for one of his squad members at Wuhan Zall. The player was represented by Li’s agency which took 50% of the new salary, some RMB 3 million ($440,000). Li also elevated three players from Wuhan Zall to the national team. He was their agent, too.

Suddenly people around the country have popped up to claim they had always known Li was greedy; they saw it when his social media posts cluttered up with commercial messages. Of course, Li has own crazy back story and it is easy to understand how he might have come to look at football, and himself, as a product to be fleeced.

An excellent defensive midfielder, he signed for Liaoning FC aged 15. A year later he was sent for training in Brazil, sponsored by energy drink Jianlibao, a disturbing adventure for all those involved.

Li was later signed by Everton for £1.6 million ($1.9 million), but he was part of a cut-price sponsorship deal with Chinese phone maker Kejian, which likely did little to help his confidence. His best period in English football came in the 2002 season when he was favored by David Moyes and the Toffees finished seventh in the Premier League. He also played for Sheffield United, and then its sister club Chengdu Blades in China. That club and its Sheffield United (Hong Kong) counterpart were both dissolved after match-fixing cases.

Li was well-respected as a player, winning 92 caps for his country and scoring six goals. But, as manager, he embarrassed officials by posting images of them eating sponsored sea cucumbers. These relatively minor transgressions are cited as reasons for the termination of his CFA contract. Fans say his limitations as a manager should have been enough.

By nature, the internet is wild and the accusations against Li Tie go far beyond football. Multiple claims have been made that Li is a bigamist, with one wife and family in the US and another in the UK. “At least they are all safe,” suggested one pragmatic club owner. Of course, you cannot unthink such things once read and you now share the conundrum of millions of Chinese fans.

It might seem strange that the Chinese government allows such speculation but the vacuum of official information that feeds it is entirely deliberate. Some reports suggest that Li has spilled the beans, others say he has refused to cooperate.

By the new year, the Chinese internet media’s vivid imagination about all feasible Li Tie schemes was exhausted. The online baying mob had already declared him guilty as not yet charged. The virtual crowds then tracked the investigators in looking higher up the chain of command. Could Li really have got away with all these frauds without protection from above?

The people and their electronic print warriors wanted the names of the “big fishes”. For those controlling the investigation, it was just a matter of when to throw them the next flailing morsels. As Chinese families prepared to travel over the Spring Festival break for the first time in three years, the men in black put their coats back on and jumped into their SUVs.

PART 2 – Chinese New Year: Perfect Time for a Spring Clean?

The Chinese Football Association Executive Committee meeting scheduled for Suzhou on January 15 was meant to review performance over the last disastrous COVID lockdown year. But that was not the main takeaway for the watching Chinese sports press.

First, Chen Yongliang, Deputy Secretary-General and Director of the National Team Management Department, vanished – even as CFA underlings were preparing his nameplate. Chen has been a key figure inside the CFA for over 20 years, so standing very close to, if not right in the middle of, the muddy corruption. He even has a criminal record.

In the 2010-2012 crackdown, Chen was found guilty of being part of a scheme to siphon off funds allocated for referee’s training. That cabal was headed by Referees’ Chief Li Dongsheng and it was far from the latter’s only misconduct. He was later jailed for nine years.

Amazingly, Chen not only survived, but continued, his rise within the CFA despite rumors of his gambling habits. When the now missing Li Tie was unveiled as the new national team manager, it was Chen who sat proudly at his side. It was also Chen who had negotiated his large salary.

But Chen’s empty chair was not the only one at the CFA meeting.

Severe Breaches of Discipline

The following day, when the meeting convened, there was an emergency resolution on the agenda. CFA President Chen, himself marked out by many online commentators as the “big fish”, led a unanimous declaration to denounce his own Secretary-General, Liu Yi.

Liu’s immediate removal from his position was a physical formality. He wasn’t there. Though it would be another four days until the official announcement that he was already in detention, suspected of “serious breaches of discipline”. Chen told his remaining team that Liu’s summary dismissal could be sorted out at the next CFA Congress. More than a few people are asking if that is in line with FIFA regulations.

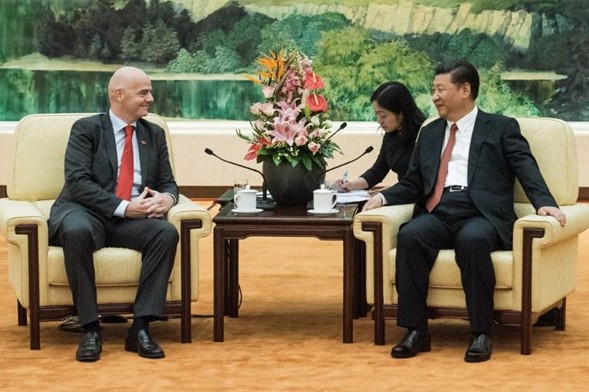

At the historic Congress set for this autumn, Chen, too, will be up for re-election. Given all these events, few in China believe he will survive. His saving grace may be that he was appointed by President Xi himself.

The fall out has already damaged China’s standing in the international game, as reported by veteran sports hack Ma Dexing. Recently, CFA Vice President Du Zhaocai failed in his re-election bid for the FIFA Council and President Chen in his efforts to get onto the AFC Council. For the first time in many years, China now has no representatives at the top levels of international football.

As for Liu Yi, he is a man widely known in international football industry circles, who counts major European leagues and clubs as previous clients.

Until he too was ‘powered off’, Liu was the first civilian (one whose career has not been within the state system) appointed to the highest echelons of Chinese football. The position is meant to come with wide operational control over CFA and CSL affairs. For that reason, it has always been a direct political appointment by the General Administration of Sport, in clear defiance of the FIFA Constitution.

A colourful players’ agent and rights broker through the 1990s and 2000s, Liu was pulled through the glass ceiling from above after returning from South Africa with IMG. The appointment of an ‘inside-outsider’ fit with President Xi’s football reforms. Liu Yi became the symbol of plans to open to external thinking.

In that role, he brought in expertise from Europe (particularly the UK) to lay the pathway to the theoretical separation of the CFA from government, and the CSL from both. When he took the job, Liu knew very well that the careers of senior CFA leaders often come to chilling ends. Like everyone in the professional game, he had no option but to work with them all. China has severe penalties for institutional corruption and he knew the score.

Given his reputation as a dealmaker through his Rhino Sports venture, there is certainly room for perceptions of conflicts of interest. That’s enough to condemn anyone these days. According to reports on Chinese media portal Sina, among the deals he was involved with were Sun Jihai’s transfer to Manchester City in 2002 and Howard Wilkinson’s appointment as Technical Director at Shanghai Shenhua two years later. A much bigger deal was Suning’s purchase of the Premier League rights for its PPTV platform. That deal collapsed and ended in court where the Premier League was awarded £157 million ($190 million) in compensation.

Irrespective of the accusations, being forcibly lifted from your place of work or home is a frightening prospect. It’s understood that his wife has received no news of him since then.

Questions Need Answers

As it stands today, nobody knows what crimes Liu Yi and the others have actually committed. However, potential clues about an even higher up “bigger fish” are starting to drip out online. According to some bolder reporters, retired Sports Bureau chief Gou Zhongwen will soon be in the spotlight.

Gou is currently respected in the industry because the country’s non-football sporting results during his tenure were relatively good. He was elected as Chairman of the Chinese Olympic Committee in 2016 ahead of the 2022 Beijing Olympics & Paralympics. After retiring, he joined the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, one of the most important government advisory bodies. People in the game say that Liu Yi has been tight with Gou’s son for years and suggest that they were involved in several “deeply corrupt projects”. So far, there is no official indication that Gou will be detained.

Not surprisingly, given precedence, very few commentators in China have even ventured the possibility that Liu Yi or any of the others might be convenient fall guys. What comes next is unknown, but the concern for those involved is palpable. What must their families and children be feeling?

So, why has this story and all the distressing disinformation been allowed to reign unfettered for so long? What are we meant to make of it all?

One key lies in the fact that this ongoing saga was launched during the festive period. It has been timed to preoccupy us from talk of (cough). The parallels with the 2010-2012 anti-corruption campaign that saw over 50 football people sent to prison cannot be ignored. That long ‘crusade’ employed the same strategy of trickle-down rumors as now. When the people in charge start disappearing, it creates a frightening silence that the masses are invited to fill with relatively harmless digital noise. Who was the ambitious Vice President who used that campaign to bolster his own public credentials? Step forward Xi Jinping.

This is not the end of the Li Tie story. And nor can it be allowed to disappear before everyone has safely reappeared and had the opportunity to speak for themselves. Last week, reporter Li Xuan implicated two women bosses working within the game. There will be more and talk this week about the detention of the head of the CFA’s Xiahe Training Base comes with accusations of sexual favors and money exchanges. There isn’t even time to mention other sports. Li Yaguang, the former Olympic basketball player who went on to become sports chief in the city of Chongqing, was also taken away in January. For now, attention is focused on the fates of those currently in detention and those now waiting with trembling limbs to be taken away at any moment.

All the chatter on the Chinese internet is now about February 9. That date will mark three months since Li Tie had his phone turned off. This is the initial time limit for detention without charge in China. The government must either charge him or let him go – or it could just extend the investigation by another three months. That would suggest that the investigators are still climbing the ladder. How far they reach remains to be seen, but it’s not a pretty scene for either of the two very powerful men that preside over this mess from above.

Xi: It’s all about our common prosperity.“

good information to broaden my horizons but if there is any other information if you can let me know